Part 1

Barry and Enid moved from Wanstead in east London to retire in Sheringham in the late 1980s. They bought a large, blue, three-story townhouse on Montague Road. The house came with the name ‘The Heuberg’, which I have just discovered is one of the hills outside Salzburg—forming part of the Alpine backdrop for the opening scenes of The Sound of Music. This map jump from Sheringham to Austria is unexpected, but the image of Maria spinning open-armed on the mountain top captures the wonder and excitement I felt getting to explore that vast house as a child.

The Heuberg was grand and large, with two front doors, a wide entrance lobby, two reception rooms—the posh room and the family room—two dining rooms, and two staircases; a wide, grand flight leading up from the entrance lobby and a dark, thin one leading up out of the back kitchen for the ghosts of the maids. Their old alarm box was still up on the wall of one of the dining rooms. On the upper two floors, six or seven bedrooms and a self-contained flat ‘up the top’.

My sister and I would spend a week or two at The Heuberg during various summer holidays from school. It always felt like we were staying in a hotel, except it belonged to our family. We got to pick our bedrooms for the week. I would pretend I lived there and Grandma would play the part of the maid—climbing the back stairs in the morning carrying trays balanced with cups of tea and marmite on toast—breakfast in bed—running us baths and spoiling us with fuss and care. I loved having my own bedroom there and remember how clean the bedsheets always felt. I had always wished that I could have been Barry and Enid’s son and that those sheets felt normal instead of a treat.

No-one ever spent much time in the posh living room after Grandma had it done up. It was all a peachy colour and it had nice new sofas that matched the walls and the carpet – you could run your hands over the fabric on those sofas brushing it the wrong way to draw pictures or write words in it. The room was always very quiet, calm and tidy. I liked to be in there. Sometimes there were lots of other family members in the house and it could get noisy and hectic - I liked the quiet.

The family room had the telly, older sofas with tassels around the edges of the cushions and the old Boyd-London baby grand piano. I remember picking out melodies on the piano and impressing my grandparents with my ‘good ear’ for it. Grandad had his chair in the corner of the room facing the telly. A harder, tall-backed chair that made you sit up straight. Beside it were racks filled with his newspapers with completed crosswords.

He was a calm, gentle and sensible man, quietly old-fashioned, and my mum and her sisters would sometimes make fun of him for it. Before he had retired he had held high-ranking positions in the metropolitan police and the social services in London after leading a group of soldiers in Burma as an officer during the Second World War. He and my grandma were lifelong Salvation Army goers and when we stayed with them we went too. Grandad played the tuba in the band, or, as he called it - the Bass. He provided the Bass in the band and was the base of the family. He had worked hard his whole life and had always been careful with the money that he had earned. Part of that money ended up helping to buy the house I live in now. Enid, my Grandma had been the caregiver and the homemaker. She made up for Grandad’s frugal nature with her generosity; she loved to share the money that he had earned and loved to save.

At the far end of the entrance lobby was a doorway to the back of the house where the kitchen and dining rooms were - this was the door that Enid would always emerge from when you arrived at the house, wiping her flour-covered hands on a pinafore before gently holding your face and plastering it with numerous tiny kisses, telling you how lovely it was to see you.

She was a lovely woman, stylish and glamorous in her own unique way and most importantly to me – an incredible grandma – the best any child could have wished for. Warm, fussy, sweet and caring. She always had time for you, or anyone for that matter. When you were out in public with her she would never fail to strike up a conversation with a stranger who happened to be sitting nearby, proceeding to proudly tell them all about her family, which was large. Barry and Enid had produced five children. One of which was my mum, but I’m not ready to talk about her yet.

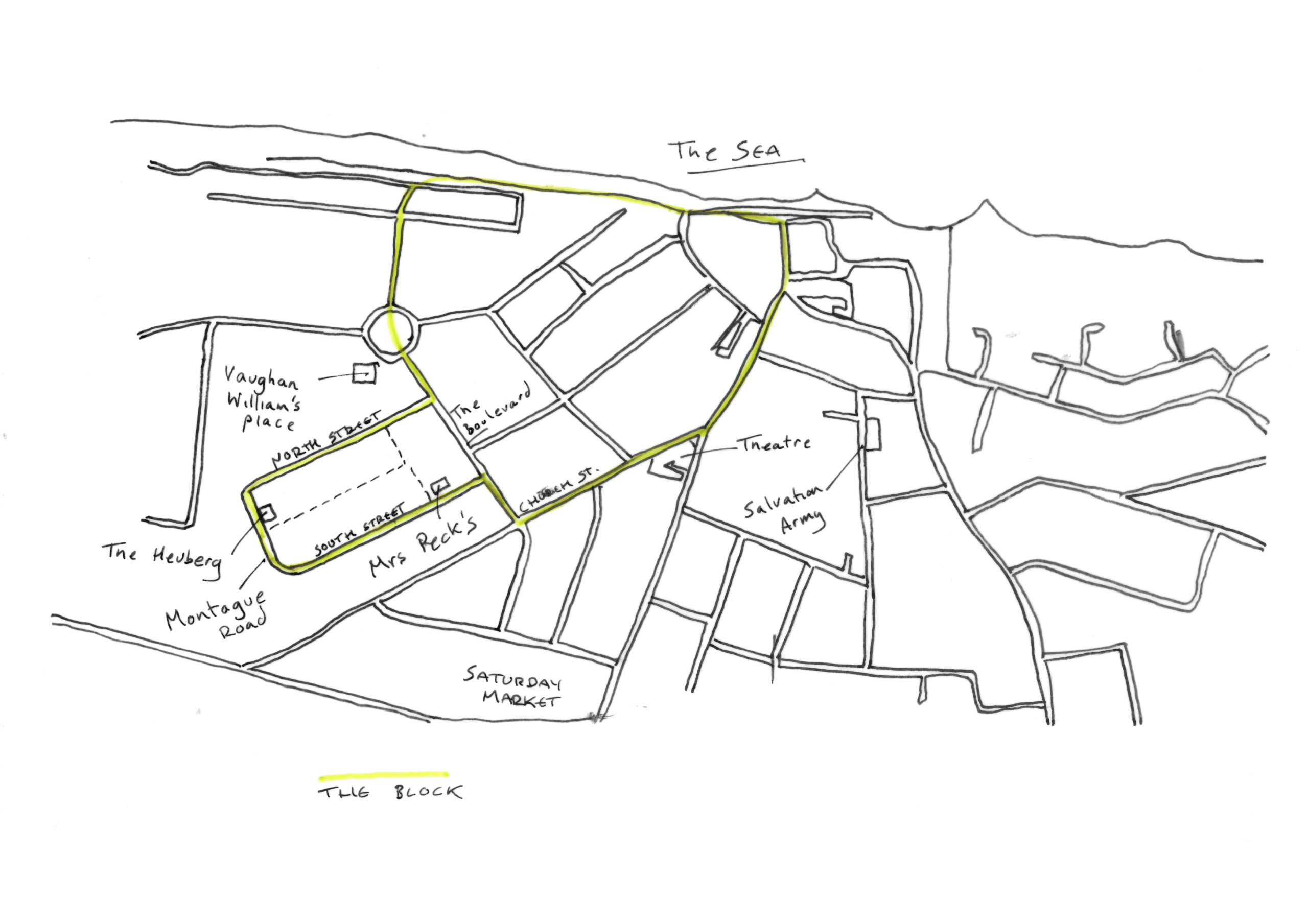

After dinner Grandad would always take me for a walk ‘around the block’. Turning right out of the front door we would race down North Street and despite his old age he would always win. We took a left down The Boulevard past the house, where according to the blue plaque, ‘Ralph Vaughan Williams’ had once lived, following the path through the middle of the roundabout with its well-kept flower beds, up and over The Esplanade and through the stone archway that framed the glorious view of the North Sea. We would take the steep slope down to the right and then walk hand in hand along the promenade with the sea on our left - long before the days of the large Norwegian boulders that litter the Sheringham beaches now, in defence against the North Sea waves.

Along the way Grandad would point out various bits of local history, like the place where the wreck of the Ispolen - a Norwegian barque that had wrecked on the beach in 1897 would occasionally be revealed or the old lifeboat station where the boat that rescued the crew would have launched from. We would follow The Promenade until it joined up with the High Street where we would turn right and walk back through the town. Taking the right fork at the little theatre to follow Church Street back to the other end of The Boulevard then taking a left into South Street and on and back up to Montague Road and the Heuberg, completing the loop. Grandad was full of stories - like the legendary ‘Jonny and the jelly’ along with anecdotes from his days in the war, like the one about the man he had met in the jungle who could talk to snakes. There always seemed to be a moral or lesson to be learned from the stories he told. They were often fantastical but he would assure you with a wink they were real and true. He was a deliberate and thoughtful man. He was also a Freemason and he had a mysterious, magical and secretive side to him.

My mum had escaped to Sheringham and the security of The Heuberg after she left my sister and I with my Dad in Ormesby. The self contained flat on the second floor had been hers while she had found herself somewhere more permanent to live. We didn’t often go ‘up the top’ (as grandma referred to it) and whilst it wasn’t out of bounds (nowhere was) it was a few degrees colder than the rest of the house, had mismatched 70s-era furniture and felt a little too far away from the comfort and safety that my grandparents provided us.

When my mum was living up there I had somehow knocked over and smashed a mirror that was resting behind the taps on the bathroom sink - tiny glass shards had filled the sink and covered the floor around it. My mum told me that I would need to own up and immediately sent me downstairs to the kitchen to explain to Grandma what I had done. Grandma wasn’t annoyed with me and immediately took the blame for having put the mirror in a place that wasn’t very safe. She did her best to remove the guilt that my mum had made me carry down the stairs. I still felt bad and in my head, I knew that this had doomed me to years of bad luck.

Fucking hell the breaks in the concentration needed to write this stuff are excruciating. My two year old son can be unbelievably difficult and annoying, even now when I’m meant to have a moment to myself to do this. This is my issue, not his, and it’s something I am trying to address through this work I am doing. I hope to write myself into a place where I can deal with him better and not cause him a childhood filled with guilt and trauma, like mine. It’s really one of the main fuels for this journey – to be a better parent – but I’m getting ahead of myself… where was I?

To be continued…